The much-delayed federal plan to manage rock climbing on the soaring cliffs of Tensleep Canyon has resumed, laying the groundwork for climbers to renew route development after a nearly six-year ban.

The U.S. Forest Service released a draft environmental assessment last week, and is seeking public comment through Jan. 20. The plan’s proposed actions include opening the canyon back up to conditional rock-climbing route development — which groups like Bighorn Climbing Coalition have long urged. That would put an end to a ban that’s been in place since 2019 in the recreation destination.

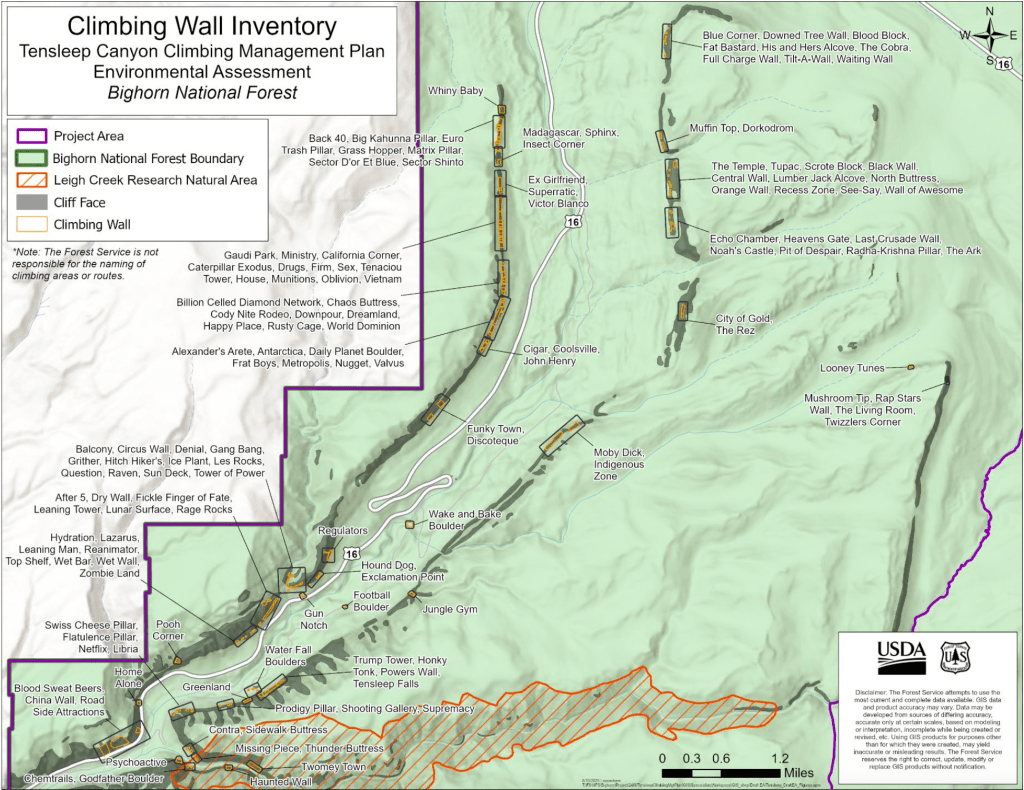

This is the third iteration of a plan that users have awaited for years. This one is accompanied by an extensive inventory of climbing routes. It lists the locations as well as pertinent conditions such as trail erosion or cliffs where the rock has been chipped away or glued — a controversial practice known as “manufacturing.”

Sport climbing is characterized by the use of metal anchors permanently bolted into the cliff face. Climbers attach carabiners and ropes to them as they ascend. The prevailing ethos among climbers is that humans should not interfere with the natural rock resource by manipulating the route to improve the climbing experience.

But without guardrails on climbing development, route building on Bighorn National Forest — and other public land — has historically occurred with little oversight, a reality that has spurred conflicts. The Tensleep Canyon plan could change that by setting development ground rules for the canyon.

The draft details steps to significantly update an area that’s been hit by impacts of heavy use including rogue trails, crammed parking lots, improper disposal of human and pet waste, erosion at the bases of cliffs and a proliferation of dispersed camping. Proposed changes include adding up to 16 miles of mostly existing trails to the National Forest Service’s network, re-naturalizing 2.2 miles of closed or rerouted trails, prohibiting dispersed camping in certain areas, installing vault toilets in four locations and designing a parking area to accommodate up to 50 parking spaces.

Under the proposed action plan, the Forest Service would close the Leigh Creek Research Natural Area entirely to sport climbing and remove all 25 existing routes there. Sensitive plant and animal species have been identified in that zone.

The plan also proposes improving staging areas — spots at the base of routes where climbers spend time while roping up and belaying — with materials like retaining walls and staircases. That proposal aims to minimize erosion and other impacts.

Starts and stops

It wasn’t long ago that Tensleep Canyon was an off-the-beaten-path climbing area. Word got out, and in an era of social media and growing interest in the sport, the former backwater half an hour east of Worland has become one of the most popular sport-climbing destinations in the Northern Rocky Mountains, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

The federal land-management agency anticipated the sport’s rise. A 2005 resource management plan predicted climbing in Tensleep Canyon would require formalized management and included recommendations to develop a management plan.

It wasn’t until a climbing conflict roiled the canyon in 2019, however, that the agency diverted energy and resources toward that plan in a meaningful way.

Climbers had discovered what they believed was widespread, manufactured climbing routes. This process of either gluing holds to the rock or chipping them out using drills or hammers can be used to turn a featureless rock wall into a climbable route. While some degree of TLC is often employed to blow out loose stones or clean up routes during development, most climbers agree that significantly altering the character of the rock is unacceptable.

A battle grew over ethical development, who the culprits were and how to make them stop. That boiled over in a nighttime raid by climbers who manually chopped bolts from rock faces and affixed padlocks to bolts.

Following these heated actions, the Forest Service in July 2019 halted the establishment of any new climbing routes or trails in the entire Bighorn National Forest. It then began work on the plan, which stands to be one of only a handful of Forest Service plans specifically focused on climbing. The Forest Service has no national-level guidance on climbing.

The district initiated a scoping process in 2021, but the process was put on ice after then-District Ranger Traci Weaver and other key players left their positions. Inventories started in 2022, and the Forest Service resumed the project in 2023. But it was paused again last year due to further turnover and a desire for more time to consult with Native American tribes.

All told, forest officials met with historic preservation and other representatives from the Northern Arapaho, Eastern Shoshone, Crow, Northern Cheyenne, Sioux and other tribes on the matter, according to the Bighorn National Forest.

What now?

The agency’s Powder River District office released the new 27-page Environmental Assessment last week. The public can view it, along with the inventory, implementation guidance and other documents, at this online project page or learn more through a StoryMap. Comments are due Jan. 20.

The project area encompasses 26,544 acres located in the southern Bighorn range between the towns of Ten Sleep and Buffalo. Though area recreators also include OHV riders, hunters and skiers, the plan hones in on climbing.

“Bighorn National Forest staff need a climbing management plan to effectively manage rock climbing … to minimize user conflict, and to protect the area’s resources,” the office stated in a press release.

The proposed actions are all designed to that end, it states. A major part of that is enacting a review and approval process for new rock climbing route development.

The proposed plan would allow route development under certain conditions. It could occur “only where rock climbing would not negatively impact wildlife and botany sensitive species,” for example. It couldn’t negatively impact traditional cultural use areas either.

In addition, the guidelines would “prohibit route development that removes rock from areas except where the rock in its natural position poses a risk to the climbing party or a future climbing party,” and “would prohibit gluing, attaching artificial holds, or using mechanical equipment to create holds where a natural hold did not exist.”

I recommend that climbers, whether sport or trad, read the draft and give it some thought. This feels like it might be the template for climbing regulation in general and sport climbing in particular on public lands. New route development will be allowed which seems like a good thing but the process and the implementation of the process haven’t been spelled out completely.

Paved paradise, put up a parking lot…….

Not too long ago I remember a Wyofile story about climbing groups being concerned that recission of the USFS Roadless Rule would destroy the solitude, serenity, and wildness of popular climbing spots like Tensleep Canyon. Ain’t that the pot calling the kettle black.

They are making a trash site out of the beautiful canyons outside of Ten Sleep!!

Im a photographer from Washakie County & have spents hrs on the mountain w/ cameras in hand. My florals/landscapes have appeared in Wyoming Wildlife, calendars & phonebook covers. But large number of climbers have destroyed, stomped down, left garage everywhere, for others to pickup & left their human waste everywhere!! To the point, the area reeks of garbage & human waste. You cant walk on any pathes or even off pathes w/ out stepping in it.

Years ago folks could enjoy this special area listed here, but after the climbers discovered it & took over this beautiful area, the locals & tourists who want to see the beauty see nothing but garbage. We’ve drive ln the old highway & the floral, landscape has been stomped down by the climbers. Only thing you can see are tents & more tents everywhere.

Than I read, park lots fot 50 cars!? Just pave over what our State is so proud of.

I understand enjoying the mountain, but not destroying the landscape/florals.

I dont know who’s making these plans, are they folks who have never stepped on the mountain or seen Wyoming? Or DC elite who have no interest in preserving the beauty of the Big Horns? The article says “off the beaten path,” no it is not. We cant take our grandkids on the Ten Sleep road, w/out apologizing for the smell & garbage when the leave. The beautiful Aspen field on the old highway has been taken over & even after they left at the end of the season, small trees were beat down, as was the flowers & grasses.

It’ll look like a Walmart parking lot.