The size of Wyoming’s proposed and controversial West Fork Dam in the Medicine Bow National Forest in Carbon County is in flux as federal environmental analysts juggle economics and conservation in a review of the planned 264-foot high concrete structure, key analysts say.

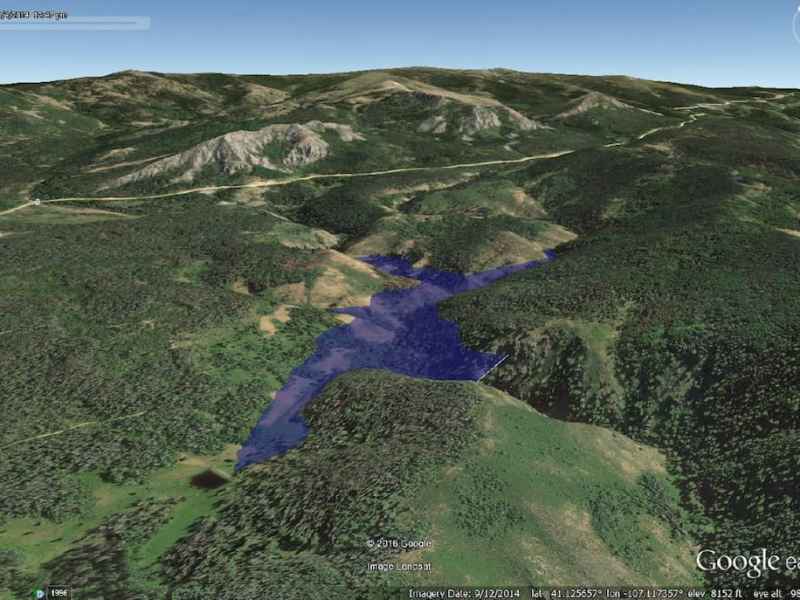

As now planned, the structure would flood 130 acres and hold 10,000-acre-feet of water on a headwaters tributary of the Colorado River Basin where drought and climate change plague a river system that supports 40 million people. The dam’s reservoir would hold enough water to supply 20,000 households for a year but it would be used principally to benefit a few dozen irrigators, federal and state documents show.

Releases from the proposed reservoir would flow down Battle Creek to irrigators in the Little Snake River Valley in Wyoming and Colorado. But Wyoming’s plan has drawn public scrutiny and controversy over its purported benefits and impacts.

Studies and analysis reveal that some parts of the plan are uneconomical, officials with the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service said last week. That’s leading the agency to consider reducing the cost and scope of the project, cutting the amount of water to be impounded and also employing irrigation conservation measures, federal analysts said.

Even as reviewers flesh out various ways to supply irrigators with late-season water, along with some public benefits and habitat improvements, Wyoming’s design remains “one of the leading alternatives,” said Shawn Follum, an engineer with the federal conservation service.

“There’s a possibility of maybe changing the scope of that dam a little bit as we’re going through some of the economics.”

Shawn Follum

As envisioned by the Savery-Little Snake Water Conservancy District, Colorado’s Pothook Water Conservancy and the Wyoming Water Development Office, the 700-foot-long dam near the confluence of Battle and Haggarty creeks would span a gorge and back up water for almost two miles.

Project backers estimated in 2017 that the entire project would cost $80 million, most of which the state of Wyoming would fund.

Some alternatives being considered in the environmental impact statement are “just not economically viable,” Follum said. “There’s no net benefit to the government.

“There’s a possibility of maybe changing the scope of that dam a little bit as we’re going through some of the economics to try to reduce some costs,” he said.

“We haven’t identified a modified West Fork [Dam] that’s practical yet,” Follum said. “But we are looking at [whether] we [can] reduce the need of the impounded water with some conservation measures, like lining a ditch to reduce seepage.”

Ongoing studies could propose a smaller project: “That’s what we’re hoping,” he said. But analysts haven’t resolved that size issue, Natural Resources Conservation Service public affairs specialist Alyssa Ludeke said.

“We just don’t have the final answer on that yet,” she said.

December deadline

A draft environmental impact statement likely won’t be completed and released for public comment until December, the two officials said in a telephone interview. The federal conservation service began reviewing the project in December 2022, coordinating with other federal and state agencies, including the Wyoming Water Development Office, the Medicine Bow National Forest and the Wyoming Office of State Lands and Investments.

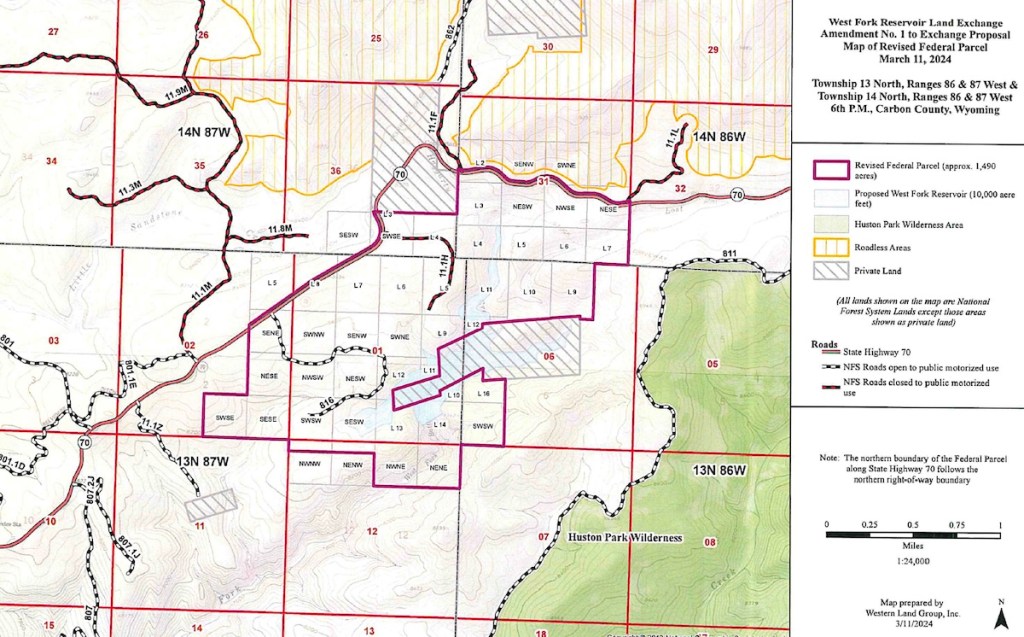

The state lands office proposed exchanging Wyoming property located inside the Medicine Bow for federal property at the dam site, a swap officials said would expedite environmental reviews. Wyoming sought 1,762 acres of federal land in exchange for an equal value of state property — until last month.

That’s when Jenifer Scoggin, director of the land office, reduced Wyoming’s proposal by 272 acres, or about 16%.

The amendment to seek only 1,490 acres was “based on discussions with the U.S. Forest Service,” Scoggin wrote Jason Armbruster, Bush Creek/Hayden District ranger with the Medicine Bow. The change “addresses resource issues” identified by field studies, she wrote.

Some of the parcels the state sought required Wyoming to surmount “larger hurdles than we could jump,” said Jason Crowder, deputy director of the state lands office.

“We’ve been working for the past year or so trying to come up with a package of land that would move easily through the federal exchange system,” he said in an interview. “It just made sense to change the make-up of the parcels involved [to follow an] easier path.”

The Medicine Bow will use the updated Wyoming proposal as the basis for a “feasibility analysis,” forest spokesman Aaron Voos wrote in an email. That finding — whether the exchange is possible — is the first of two steps.

If the swap is feasible, the Medicine Bow would then determine whether it is in the public interest.

Alternatively, the environmental review might suggest that the state construct and operate a reservoir under a federal permit instead of acquiring the land underneath and surrounding the dam and reservoir. Wyoming has not favored that path.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Forest Service continue their independent reviews.

“I believe the land exchange will probably be slower than the EIS itself,” Follum said. “But that won’t impact [us at the conservation service] because we’re going forward with the kind of a dual assumption; it’ll either be a land exchange or permit.”

The conservation service identified six alternatives when it announced its environmental review, including a no-action alternative. Three other alternatives consider building the dam as proposed under a Forest Service permit or through a land exchange. A fifth option calls for locating a reservoir elsewhere and a sixth calls for water conservation and habitat-improvement projects.

A better use of these monies would be to rebuild the canals in the Little Snake River Valley to minimize seepage and waste. The amount of money needed to repair the existing ditches would be far less, and a far better use of funds. To destroy one of the last pieces of untouched Lost creek, which contains numerous waterfalls, is not the “legacy” that I want to leave behind for my children.

I am against any land swap.

What are the prospects for hydro electric generation?

This seems like a government handout to a few dozen irrigators as a taxpayer this doesn’t benefit me at all just a few dozen irrigators i say it’s not needed I assume they’re irrigating hay they just want more cuttings and want the taxpayers to pay so they can make a bigger profit pretty greedy I say kill it

I’m not a fan of Wyoming paying so much to benefit a few dozen irrigators. That does not seem to be good stewardship of taxpayer dollars. The only benefit I see to the greater population is as a resevoir for forest fire aircraft to draw from in the area.

Rather than throwing away $80 million to subsidize a marginally profitable industry that has damaged land quality, water quality, wildlife, government integrity, and public health for many years, perhaps the state should simply purchase the ranch land in question and turn it into a wildlife reserve, providing winter range for elk and other species.

I have a novel idea, how about the users of this water diversion come up with 10% of the cost? I bet that this will disappear with a whimper when they have to pony up their own money, or borrow it and pay it back…

Water. The next big fight in the state & with surrounding states. It’s past time to start talking & planning.

Hardly the “next big fight”. Water has constantly been fought over for over a hundred years in Wyoming. That’s why the 1904 Water compact was drafted. It’s time for it to be amended due to changing population and water level conditions. Unfortunately, that’s a slippery slope. Wyoming should ask to have less water sent to lower basin states (as a head water state) that are squandering it, but more than likely they will get more because of greater population density. Arizona is crying Upper basin states need to provide them more water, but they sure dont stop filling swimming pools and watering golf courses to conserve what they are given.

although i did not vote for you,

your brief analysis is spot on.

well said !

My preference is “……sixth calls for water conservation and habitat-improvement projects.”

I also agree to the 6th option.

So, I know what’s in this for the irrigators, but why should the public support this dam? It’s going to have a lot of negative impacts so where are the positives? Why should the public want a dam to be built on public land? What’s in it for them?

Just say NO! We don’t need anymore boondoggle projects. When the rest of the country is tearing down dams, Wyoming wants to build more. We should not support Colorado irrigators, and the decimation of a live stream.

I agree with you in context. But “the rest of the country is tearing down dams” is mostly because they are old, decrepit and dangerous. That’s not a good argument … but I agree with your sentiment.

Kill it, don’t downsize it! The vast majority of public comments were against the project…still they persist. Doesn’t public opinion mean anything to them?